“The prophets of new media forecast widespread democratisation of the world’s media systems. Thus far, the impact of digitalization and convergence on the public sphere has been disappointing.”

Drawing on some of the key theoretical perspectives, give your own verdict on the impact of new media as well as comparing and contrasting it with old media.

New media is a nebulous term. There is no concrete way as to define what exactly is new about this particular media. In common use, the term is attributed to media that have recently been developed or are emerging, in contrast with old media which have existed for a longer period of time. However, like television can simply be seen as a radio with pictures, new media can be seen as old or already existing media (print text, photographs, films, recorded music, television) simply “repackaged” in a digital format (Bolter and Grusin, 2000). Sonia Livingston states that there is more to the term new media than simply meaning media that are recent; it is more closely related to the changes evoked in society as a result of the introduction of this new media. In other words, the question is not just “what are the new media?” but more particularly, “what’s new in society about the new media?” (Livingstone, 1999:60). Although new media can refer to a range of digital forms of media, the most prominent example is the internet. The substantial impact the internet has had on democratisation and society is yet to be surpassed by any other new media. In fact, most discussions and academic references to new media all essentially focus on the internet, as it dominates the widely accepted definition of new media.

The content of digital media is not necessarily new, as it merely reproduces old media. The question is then: what actually makes new media ‘new’? As Livingstone pointed out, it is in fact the social impact of the media, or the way in which it has changed society, which is considered ‘new’. Technological innovation or ICTs (information and communication technologies) possessing the power to shape society is known as technological determinism. The internet, and ICTs in general, exhibit many of the characteristics which allow it to fit this theory.

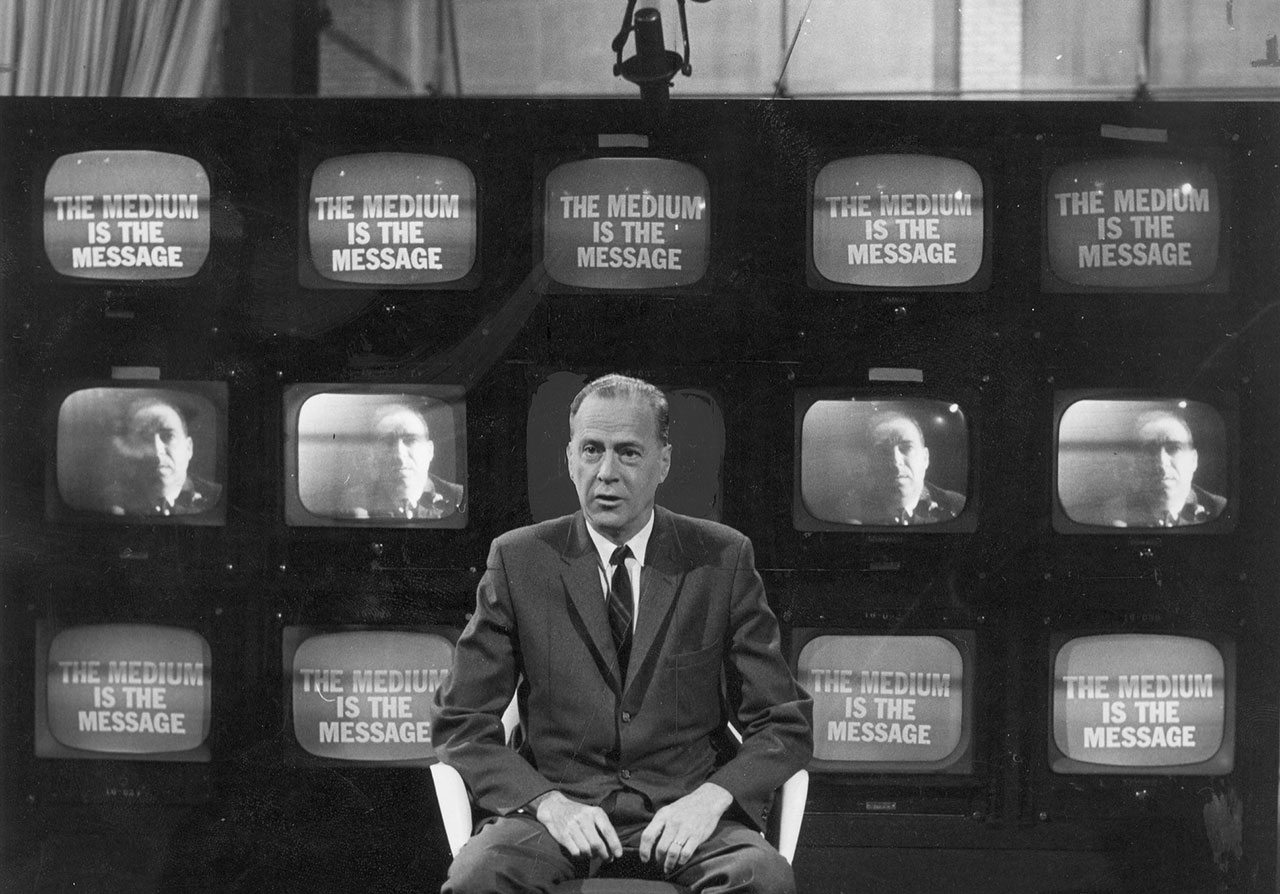

Marshall McLuhan believed that “the medium is the message” (McLuhan, 1987:7). He believed that the form in which the message takes influences the message itself. However, not only did McLuhan believe that the medium influenced the message, but it also had a dramatic influence on the society in which the message was being delivered. McLuhan could therefore be considered a technological determinist (O’Shaugnessy, 2005:438). New media, particularly the internet, have been the driving force behind globalisation and ‘the global village’ – a term coined by McLuhan (McLuhan, 1962). Technology such as the internet has allowed the world to theoretically ‘shrink’. Ever since the invention of the telegraph in 1840, distance has had a decreasing significance, but it was the arrival of the internet which was declared the “death of distance” (Cairncross, 1998). As a result, people were no longer separated by distance, forming virtual communities or ‘global villages’. Virtual communities demonstrated how networked media “enabled forms of community to emerge that transcended geographical barriers” (Flew, 2002:26). Online communities tended to be “not of common location, but of common interest” and “life would be happier for the online individual because the people with whom one interacts most strongly would be selected more by commonality of interests and goals than by accidents of proximity” (Jones, 1998:19). New media are the key to bringing the world closer together.

One of the relevant features of new media is convergence – the way different forms of media, originally stand-alone, are now gradually being accessed through one universal medium. In the seventies, signals for televisions and radios operated over airwaves, telephones operated over their own network lines and computers were stand-alone devices. Nowadays, computers, previously disconnected from any other medium, can be used to stream audio and video, and also communicate through voice chat (Flew, 2002:18). O’Shaughnessy has stated that convergence “can lead to sensationalism, trivialisation, generalisation, recycling of content and lack of diversity of information”, but on the flip side, it can also “enrich communication by providing more options for senders and receivers of messages and by enabling the creation of multi-model texts that combine a variety of media-forms” (O’Shaughnessy, 2005:437). The positive and negative aspects of convergence can be interpreted as a reflection of what is positive and negative about globalisation. Sure, a negative point of view could be that new media simply recycle old media in a digitised format (as mentioned earlier by Bolter and Grusin), but it is difficult to imagine how this could outweigh the vast number of positive aspects brought about by new media, such as the enrichment of communication. Improving communication and methods of communication is not something to be underestimated, especially for areas where democracy is being hindered by society.

Even though new media, particularly the internet, provide a platform for discussion (that is, the public sphere, later discussed), the system is not entirely democratised as it still faces the problem of the digital divide. This is defined as the boundary separating those with access to ICTs from those who do not. It has become a major problem of globalisation because even though ICTs provide the opportunity for democratic participation, it still excludes, albeit unintentionally, those without access due to social, economical or democratic factors. However, in the long run, the positive aspects will overcome the negative. The digital divide shall soon be a problem of the past, as internet access is vastly expanding in developing nations (Porter, 2005).

One of the major positive impacts of new media is the freedom associated with the internet. Publication through virtual communities and ‘cyberspace’ is unbound by the gate-keeping traditionally associated with old media. Gordon Graham has said that the emergence of ‘cyberspace’ has led to “the suggestion that we are on the verge of a new kind of reality – virtual reality – in which we will become possessed of the power to create for ourselves a world of experience which is free from the limits of ordinary contingency” (Graham, 1999:19-20). Newspapers and televisions have many ‘gatekeepers’, such as editors and producers, who are selective about the material printed or broadcast, so the news is always in accordance with what they believe is important.

New media can deliver information “without the gatekeeping influence of editors” (Tambini, 1999:311), thus having a positive impact on democracy. The phenomenon which typifies this idea of the freedom of new media is the advent of the weblog. Weblogs, or simply blogs, are “web-based publication consisting primarily of periodic articles” (Wikipedia, 2006). Blogs are a common alternative to traditional print and televised news sources; the main perceived advantage being that it is ideally untarnished by ‘gatekeepers’, such as editors and producers who may have hidden agendas influencing their selection of content.

This is not to say that blogs are completely reliable, but when content fed to us by old media is questionable, it is essential to seek different, and more importantly, uncensored views in order to balance the truth. The quintessential example of this is the media’s depiction of Iraq war. As described by Michael Tolvo from sixosix magazine in an interview with Riverbend, a blogger from Baghdad, the portrayal of Baghdad as a city on American television has been grossly distorted:

“Americans are delivered news of daily atrocities in Iraq from our televisions, radios and newsstands. The American public has been made well aware throughout the war that what is displayed on the nightly news can be digested as information weighted by stereotypes, by government media regulations, by our own ignorance of Iraqi culture, each impeding our understanding of Baghdad as a contemporary city with identifiable traits, not unlike our own idea of a city.”

The stark contrast between the depiction of Iraq through old media and new media highlights the impact new media has had on journalism (and ultimately, democracy). Old media, such as “televisions, radios and newsstands”, depict Iraq using misguided stereotypes to present a kind of lack of civilisation, which is expected in a situation such as war involving the home country, since part of glorifying their own nation would be to diminish that of the opposition. New media provide a way for people to see, not necessarily the definitive truth, but at least a different perspective which eliminates the questionable nature of gatekept news. Also, blogs, due to the unrestricted nature of their content, can be more reliable in breaking particularly sensitive news that would otherwise be reported after a period of selective alteration by the press. A notable example is the Lewinsky scandal, which the Drudge report, a political blog maintained by Matthew Drudge, broke news of on January 17th, 1998 – four days before it actually reached mainstream press (Wikipedia, 2006). This again reflects the gradual control of news slipping from the press into the hands of citizens.

Providing an alternative view or ‘truth’, especially when the truth is distorted by the media, gives citizens a more democratic view of their society. However, some governments want more control, and prefer to withhold this right to democracy from its citizens. The best global example is Asia. The media in many Asian countries is under considerable regulation and heavy censorship. China and Malaysia are among countries where new media have become a threat to the government’s “monopoly on the truth”. Steven Gan, a Malaysian journalist, is known for starting Malaysia’s first and only independent media outlet, Malaysiakini, after he decided that he was “getting a bit fed up with the level of censorship in the mainstream media” (Neumann, 2000). The site has been widely acclaimed, and has since received the Free Media Pioneer 2001 award from the International Press Institute and the Committee to Protect Journalists’ International Press Freedom Award 2000 (Gan, 2001).

Despite the amount of censorship in mainstream media in Malaysia, the government has not yet outlawed publishing alternative news content on the internet. In China, however, a ban exists. The Chinese media “have been little more than heavily censored government mouthpiece” (Griffiths, 2005), and since the emergence of blogs, the government’s control over the media has been under threat. As a result, the government has reacted violently, imparting severe punishments on those providing or accessing content that could harm or challenge the government. In 2001, the death penalty was introduced for providing state secrets over the Internet (Amnesty International, 2004). In 2003, in its censorship bid to target blogs, China sentenced Tao Haidong, an Internet activist, to seven years in prison for publishing articles critical of the Chinese government (ABC Online, 2003).

Despite all attempts to censor the internet, the government is said to be “starting to lose the battle over internet control” (Griffiths, 2005). The internet is expanding at a rate which is making the task of regulation almost impossible for the Chinese government, among many other Asian governments. With the expansion of different types of communication, it can be considered impossible to completely block access:

“You’ve got satellite phones that can phone into the mountains of East Timor… you can’t block the news. They turned the phones off; they turned off the mobiles phones and the turned off the landlines, but Indonesia couldn’t turn off the satellite phones.” (Williams, 2000)

New media provide uncensored, undistorted news with varied perspectives for citizens to formulate their own opinions. On top of this, there is also the opportunity to interact. The internet provides a platform or space for political discussion and opinions that would otherwise not exist, which is clear evidence that new media is a significant aid in shaping the emerging democratisation of nations. The existence of these spaces was an idea first introduced by Jürgen Habermas, who coined the term public sphere (Habermas, 1962).

New media have had a substantial impact on the public sphere. Golding says “we find ourselves staring at the arrival of a tool that could nourish and enhance the public sphere…” (Golding, 1996:85). More people have become involved in political debate as a result of this newfound ability to voice themselves. The unrestricted, interactive and highly accessible nature of the internet is the main reason why citizen participation has become more prevalent. Another reason for the expansion of the public sphere is that, as Tambini argues, the growing advancement of new media “remove[s] potential barriers to participation because [it] reduce[s] the costs – in time and money – of taking part.” (Tambini, 1999:311). New media, or the internet in particular, are a driving force behind the public sphere due to “their capacity, their interactivity and their freedom from time-space constraints” (Poster, 1998). Greater interactivity is the key determinant in distinguishing old media from new media in terms of the public sphere. Despite newspapers and radio shows allowing for letters and callers, there are still editors and call screeners; bulletin boards and internet forums eliminate this selectivity:

“A convergence of opinion from both left and right asserts that newspapers, radio and television distort and trivialize democratic communication. Others have made the small step from this prognosis to the assertion that new media… can be used to encourage active political citizenship.” (Tambini, 1999:305-306)

New media have opened up opportunities for increased democratisation, due to the flexibility, accessibility and relative ease nowadays of being able to set up a website. The internet has also provided a platform for people to voice themselves more easily and anonymously (for example, Riverbend), meanwhile still informing people and making a difference. News is being delivered in a manner which has the audience being more involved and selective about what they want to be informed of, as opposed to television and print media in which the press has power over the readers’ idea of what issues are important. New media have emerged as a tool for democratising states where the old media is controlled and consequently heavily censored. George Glider expressed the “moral corruption of mass media and culture” associated with television by describing it as “a tool for tyrants”, meanwhile praising new media for its promotion of “a new era of creative capitalist individualism” and “freedom and individuality, culture and morality” (1994:49). This is especially true for a country like China where the internet has become a power to undermine and overthrow the government’s monopoly on the media. Neil Postman coined the term technolopy to summarise what could be considered as technological determinism from an extremist point of view. Postman describes the term as “the deification of technology, which means that the culture seeks its authorization in technology, finds its satisfactions in technology, and takes its orders from technology” (Postman, 1993:71). People have deified, sought satisfaction and taken orders from media, old and new, since it came into existence. The only difference is that new media allow the people to choose, sometimes even create, what they want to deify, seek and take orders from, and in a utopian society, this would be democracy.

Bibliography:

(April 20, 2000) “Asian Media.” Media Report Retrieved 2006, June 1, from http://www.abc.net.au/rn/mediareport/stories/2000/120341.htm.

(2003) “China’s Internet Timeline.” Amnesty International, from http://www.amnesty.org.au/airesources/newsletterfebmar03/ap04.html.

(2004) “China targets weblogs in censorship bid.” ABC Online, from http://www.abc.net.au/news/newsitems/s1068965.htm.

Bolter, J. D. (2000) Remediation: Understanding New Media. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Cairncross, F. (1998) The Death of Distance: How the Communications Revolution will Change our Lives. Orion Business Books, London.

Flew, T. (2002) New Media: An Introduction. Oxford, Melbourne.

Gan, S. (April 29, 2001) “Ending the government’s monopoly on the truth.” The Observer Retrieved June 1, 2006.

Glider, G. (1994) Life After Television. W.W. Norton & Co., New York.

Golding, P. (1996) “World Wide Wedge: Division and Contradiction in the Global Information Infrastructure.” Monthly Review. (July-August): 70-85.

Graham, G. (1999) The Internet: A Philosophical Inquiry. Routledge, London.

Griffiths, D. (2005) “China’s breakneck media revolution.” BBC News Retrieved June 1, 2006, from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/4156458.stm.

Habermas, J. (1962) The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Jones, S. G. (1998) “The Internet and its social landscape”, in S. G. Jones (ed.) Virtual Culture: Identity and Communication in Cybersociety. London, Sage.

Livingstone, S. (1999) “New media, new audiences.” New Media and Society. 1(1): 59-68.

McLuhan, M. (1962) The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man. University of Toronto Press, Toronto.

McLuhan, M. (1987) Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. Ark, London.

Neumann, A. L. (2000) “Interview with Steven Gan of Malaysia CPJ International Press Freedom Award 2000.” CPJ Press Freedom Online Retrieved June 1, 2006, from http://www.cpj.org/awards00/gan_interview.html.

O’Shaughnessy, M. and J. Stadler (2005) Media and Society: An introduction. 3rd edn, Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Porter, C. (October 28, 2005) “Expanding Internet Access Must Remain Focus at WSIS Summit.” The United States Department of State Retrieved June 2, 2006, from http://usinfo.state.gov/eur/Archive/2005/Oct/28-406726.html.

Poster, M. (1998) “The Internet and the Public Sphere.” Virtual Politics.

Postman, N. (1993) Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology. Vintage, New York.

Tambini, D. (1999) “New media and democracy.” New Media & Society. 1(3): 305-329.

Tolvo, M. (2004, March 28) “One of those countries.” sixosix magazine Retrieved 12, from http://www.606mag.com/main.php?id=132.

Wikipedia. (June 1, 2006) “Blog.” Wikipedia Retrieved June 1, 2006, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blog.

Wikipedia. (May 30, 2006) “Lewinsky scandal.” Wikipedia Retrieved June 1, 2006, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lewinsky_scandal.